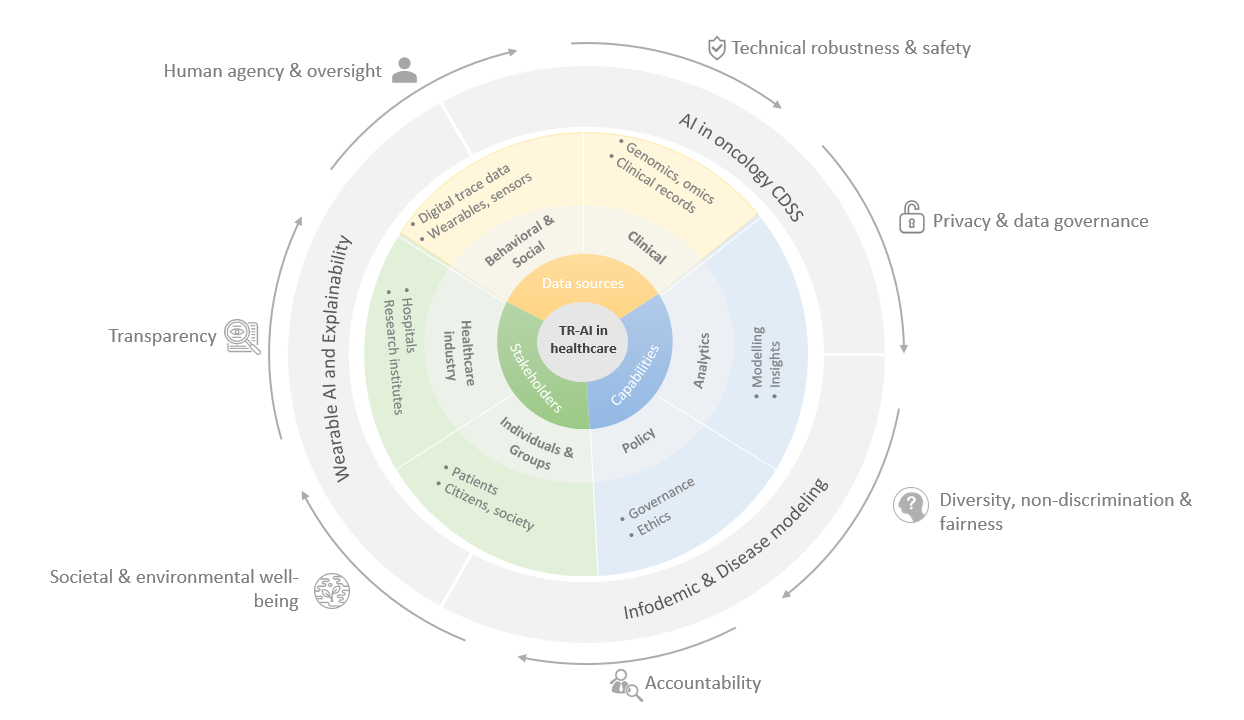

Trustable and Responsible AI (TR-AI) for decision support in healthcare (Habilitation Project)

The habilitation project aims at increasing trust and reliability of the usage of AI in the healthcare sector. The focus is set on three use cases, each dealing with different aspects of trustworthiness.

Use Case: Wearable AI in Healthcare

Wearable devices such as smart watches have been around for a decade, and while they used to be less accurate in the beginning, nowadays there are various wearable devices that are used not only by health enthusiasts but also by patients especially for remote monitoring purposes. While the devices’ design and functionalities have been improving over the years, AI has also developed steadfast in the last decade. Nowadays, wearable have the potential to fuel artificial intelligence methods with a wide range of valuable data (Nahavandi et al., 2022).

In healthcare, there is an enormous potential to use the patient data generated from wearables. For the medical experts, using these data means understanding disease progression much better by having access to non-biased data, as well as improving overall disease prediction and treatment. Wearable devices will continue to improve in form and functionality and their usage in healthcare scenarios is predicted to increase in the future. A major driver for this is the workforce shortage in the healthcare sector. Healthcare workers are increasingly overwhelmed, and there are not enough medical professionals even in developed countries such as the UK. The problem will only exacerbate in the future.

Although existing research points out the potential benefits of wearables in healthcare, there are still significant challenges that need to be overcome.

- Variables – which variables from the device should be used in the chosen context? E.g., is the “average steps per day” metric relevant for an oncology patient or is another metric necessary?

- Data quality – how can data from a large number of patients (using different devices) be used simultaneously? Some options for future research are technologies such as Federated Learning, and the question of interoperability.

- Data processing and analytics – how would the data be processed? E.g., on each device separately, and then used for improving a global ML model? What type of algorithms would be most suitable for making sense of the data?

- Data interpretation – how can the data be visualized and interpreted, both by patients and experts?

Use Case: AI in Oncology CDSS

There are few studies done directly focusing on the opinions and difficulties experts in the medical field experience when it comes to using AI for decision making. The EU, USA, Australia, and other countries have taken steps to establish regulatory frameworks for the implementation and use of AI systems in sensitive domains. However, translating these regulations into practice is not a straightforward process. Even if we take one aspect of trustworthiness, e.g., explainability or interpretation of AI models, we find ourselves already challenged by defining explainability – research shows that different people view explainability in different ways. Thus, it is of great relevance to hear directly from the experts on the challenges they are facing, and it is necessary to develop solutions tailored to a specific domain (as in this case oncology) instead of offering general solutions to a multi-faceted issue.

The proposed study aims at defining and addressing the challenges which medical decision makers are facing when using AI-based systems. The focus is on the oncology domain, and the identified challenges are mapped to the trustworthy and responsible AI dimensions. Oncology is the chosen domain, as cancer is the leading cause of death worldwide according to the World Health Organization and, therefore, many AI solutions have been developed for diagnosis (especially with images), screening and treatment.

Use Case: Infodemic and disease modeling

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an infodemic as “too much information including false or misleading information in digital and physical environments during a disease outbreak” (WHO, 2022). Misinformation as a concept has been defined in several ways in academic research, with the most widely used definition to be given by Lewandowsky et al. (2012) – “any piece of information that is initially processed as valid but is subsequently retracted or corrected”.

Most experts agree that in the future we will be likely facing another pandemic which warrants a better preparation and more research on ways to tackle it properly – not only from a medical perspective but also considering misinformation. Therefore, social and behavioral scientists need to work in cooperation with health and computer science experts to find innovative solutions to diminish the consequences of a future infodemic.

Previous research has built mathematical models for disease transmission modeling. Agent-based models are often used for simulation purposes in this regard, especially for testing the impact of various measures such as e.g., vaccines of non-pharmaceutical interventions. The next line of research is to combine traditional methods used in digital epidemiology with machine learning, as well as integrating social and behavioral dynamics for a more comprehensive and more accurate policy guidance and response measures (Bedson et al., 2021).

Researcher

Partner

References

Bedson, Jamie; Skrip, Laura A.; Pedi, Danielle; Abramowitz, Sharon; Carter, Simone; Jalloh, Mohamed F. et al. (2021): A review and agenda for integrated disease models including social and behavioural factors. In: Nature human behaviour 5 (7), S. 834–846. DOI: 10.1038/s41562-021-01136-2.

EU Commission (2019). ETHICS GUIDELINES FOR TRUSTWORTHY AI. Online. Available at: https://www.aepd.es/sites/default/files/2019-12/ai-ethics-guidelines.pdf

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

Nahavandi, D., Alizadehsani, R., Khosravi, A., & Acharya, U. R. (2022). Application of artificial intelligence in wearable devices: Opportunities and challenges. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 213, 106541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106541

WHO (2022). Infodemic [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/health-topics/infodemic#tab=tab_1